The mayor who gambled on community heat — and lost

Geothermal district heat could be a great tool for fighting both emissions and energy costs. Can it win communities over?

There’s a lot to love about district heat. New York’s climate planners certainly think so.

We have the workforce to do it. We have the technology. To me, the big question is: Do we have it in us to cooperate?

I’d like to tell you a story about how district heat flipped a local election. I’ll get to it. First, a little context.

As I’ve written many times: Building HVAC is New York’s biggest climate problem by volume, making up about a third of the state’s greenhouse gas emissions, and one of the toughest to solve. Zero-carbon geothermal community heating districts would go a long way toward tackling that problem, if they can get off the ground in the first place.

Earlier this year, New York State enacted the Utility Thermal Energy Network and Jobs Act, aimed at accelerating the development of zero-carbon community heating systems in dense neighborhoods across the state. The law requires all seven of New York State’s major utilities to develop pilot projects that will serve as laboratories for working out the kinks in community heating systems — not just in technology and logistics, but in what kind of regulatory frameworks and billing practices make systems like these function well.

For a climate law, this one is deeply uncontroversial. The bill passed the state Senate in a unanimous 63-0 vote. Utilities and labor unions that have pushed back hard against “all-electric buildings” legislation, which would set a timetable for phasing fossil fuel heat systems out of new construction, lined up in support. For utilities, UTENs, as they’re known in state acronym-land, are a chance to run a new kind of business. For gas utility workers, who already have a lot of the relevant skills, they’re an opportunity to make a pretty seamless transition from good union jobs in the fossil fuel industry to good union jobs in zero-carbon energy.

As a “town” dweller myself, living in a fairly dense village center surrounded by miles of rural forest and farmland, the idea of having community geothermal heat and hot water is very attractive to me. Predictable heat costs? Less infrastructure in my own house? No more emergency calls to the plumber because the water heater that was fine yesterday is suddenly leaking expensive hot water all over my basement floor? Sign me up. But not everyone feels this way — and for community heat enthusiasts, it’s worth taking a good long look at how community support can make or break a project like this.

I had a chat about all this recently with my pal Todd Pascarella, former mayor of the village of Fleischmanns. Along with Margaretville, it’s one of two villages in the Delaware County town of Middletown, where I live.

Fleischmanns: A beautiful mess

For a village of fewer than 300 year-round residents in overwhelmingly-white upstate New York, Fleischmanns is a place with a lot of cultural diversity. It’s home to a few different Central American immigrant communities, who make up a lot of the village’s younger population, and home in the summertime to a large Orthodox contingent from downstate as well. The village got smashed to pieces by the Irene floods in 2011, and then inexplicably left out of Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s New York Rising flood resilience program afterward. It’s a place of fractious politics, weirdly grand history, a relentless rumor mill, and a stubborn streak of resilience in the face of disaster. It’s a whole world in a few crumbling blocks.

There’s a big messy story to tell about little Fleischmanns, and honestly, it deserves a book. But for now, I wanted to focus on the quixotic effort to bring district heat to the village back in 2014, and what lessons it might hold for the next generation of community systems.

Full disclosure: Todd has been a personal friend of mine for years, and we’ve both hired each other. Todd co-founded the Union Grove Distillery in Arkville where I used to bartend on weekends. He’s also a contractor who used to work with NYSERDA’s confusing and red-tape-laden loan program for home weatherization, and I credit him with getting me through that process without having a stress aneurysm. Todd was a great champion of the Fleischmanns district heat project, and it might have cost him a local political career.

Here’s the story of how that happened.

About a decade ago, SUNY’s College of Environmental Science and Forestry was looking around for a community to do a pilot project in, to see if district heat powered by locally-produced wood chips was a viable idea in rural upstate New York. The way Todd tells it, they reached out to Jim Waters at the Catskill Forest Association, headquartered in nearby Arkville. Jim, in turn, talked to Fleischmanns village officials, and they got excited about it. And lo, an idea was born.

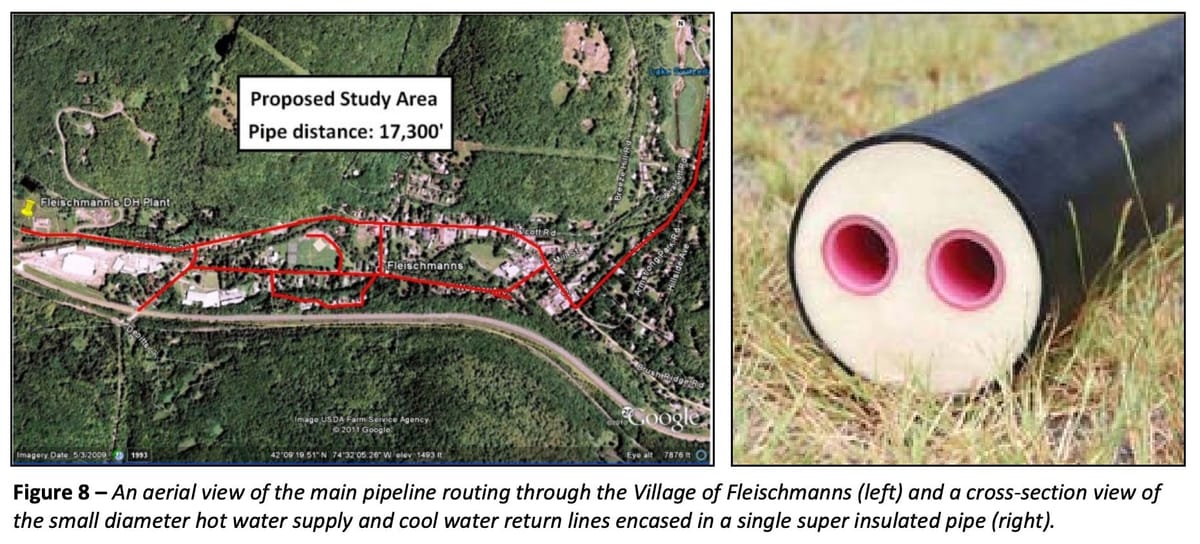

In 2013, with support from SUNY ESF, a Vermont nonprofit called the Biomass Energy Resource Center did a feasibility study laying out how Fleischmanns could heat homes and businesses in the village center with a wood-fired plant, how much it would cost, what impact it would have on air pollution and carbon emissions, and what grants might help fund its construction. Todd gave me a copy of the study, and I’ve posted it on Scribd, because it seems to be unavailable on the internet.

The Fleischmanns district heat study has got to be one of my top five Ambitious Catskills Studies That Never Went Anywhere — up there with Delaware County’s 2011 public transportation plan, a document I find both enraging and hilarious. It was the talk of the town for a year, it got a slick promotional video from the Catskill Forest Association, and then it vanished as though it had never existed.

Q&A edited for length and clarity:

Empire of Dirt: Wasn't the original inspiration for the Fleischmanns project a campus?

Todd Pascarella: Originally it was just to do a study. It was to find a location they could study, which had some potential to progress to a project, because they didn't want to study something that could never go anywhere.

We took a field trip out to Connecticut to Hotchkiss School, which is a prep school. They had just switched over to such a system with these giant wood chip boilers. A bus full of people from Fleischmanns and other stakeholders — we took a ride out there and saw their operation. It was pretty impressive.

What we needed to do was start communicating what the potential of this was with the public. The key thing eventually was to get everyone to buy in. There was no chance that it was just going to be imposed. We saw a huge potential benefit for everyone. Rather than us all having our own huge septic field on our property, which a lot of people can't even fit in a place like this — you know, let's have a central sewer system? Well, let's have a central heating system and get the economies of scale of that. And by the way, we get to use this local, renewable energy source as opposed to buying freaking oil.

I thought the comparison to public sewer systems was tragically apt. Not far away, in the hamlet of Phoenicia, plans for a largely New York City watershed-funded wastewater treatment plant fizzled out after a long campaign by a couple of local business owners to sow fear and opposition to the project. Phoenicia’s lack of public wastewater treatment is suppressing development, and has even made it tough to get a loan for a business in the hamlet.

The Fleischmanns project met much the same fate: defeated not by any clear decision on the part of the community or its government, but by suspicion and inertia.

TP: The rubber met the road. Part of that's probably my inability to communicate all of that without it seeming overwhelming or scary or whatever — but there were a lot of people who, for both good reasons and for really not legitimate reasons, got their hair up and were against it.

It just got to be this game of telephone. It got lost in translation. Eventually we just really couldn't stay on top of it anymore. And I got unelected.

In March of 2015, the first village election held after the heating project was proposed, Todd lost to challenger Donald Kearney, 33 to 42. In Fleischmanns, a nine-vote difference counts as a landslide.

Todd told me that no matter what he said, a lot of people assumed he would personally make money off the project because he was already working with NYSERDA. For some, that was a reason to be suspicious.

ED: I'm curious whether you think the sentiment about it broke down along right-versus-left lines, or whether it was different. I remember Jen Kabat was always laughing about this project, calling it “Republicans do socialism.” But it always struck me as an example of how local stuff is different, you know? It doesn’t fit in any box.

TP: It absolutely didn't break down into any kind of tidy left or right thing. There were people who were skeptical about village government to begin with, and really vocal about suspicions of how there must be something else to this. It can't just be that you want to save energy and use locally sourced renewable fuel for heating the village. What are you really trying to do to us?

We didn’t realize how threatened it would make people feel.

Technology is only half the battle

I was thinking about Fleischmanns last week, when I sat in on a technical conference held by the state Department of Public Service to talk about community geothermal heat systems. State utilities gave short presentations about the pilot projects they’re working on, and geothermal professionals were there to talk with state regulators about the challenges of rolling out projects.

Those challenges are pretty steep — and the pros in the room were well aware of them.

“Moving into this space is going to require a lot of collaboration between the utilities and our communities,” one Central Hudson representative said. To put it bluntly: After widespread billing problems that have sparked a state investigation and roiled the utility’s customer base throughout the Hudson Valley, Central Hudson is a long way from having the trust of the public on forward-looking collaborative projects.

One very cool aspect of UTENs is that if they are built in a place where a large industrial building makes a lot of waste heat — for instance, a factory, or a data center — that building can “pay” heat into the community system for others to use. But, as one geothermal expert pointed out, just because it’s technically doable doesn’t mean people will be eager to embrace it.

“Nobody wants to be responsible for their next door neighbor's hot water and heat,” said Zach Fink, president of ZBF Geothermal on Long Island.

It must be said: Geothermal community heat, delivered by ground-source heat pumps, is a cleaner and more unambiguously climate-friendly technology than heating with wood — or any fuel that needs burning. Any project claiming climate benefits based on the use of renewable wood fuel deserves tough scrutiny, from regulators and from the community.

But the Fleischmanns project didn’t fail because people were worried about wood smoke or overhyped climate claims. It failed because new stuff is scary and cooperation is hard.

A lot of the community heat pump pilot projects that are currently underway in New York are on college or hospital campuses, or other places where a single building owner makes up all or most of the heating district. If those projects go well and can demonstrate good results for the people who live and work in the districts, maybe they’ll make it easier for UTENs to expand into more difficult territory.

If not, we may see more projects go the way of Fleischmanns community heat: mothballed before a vote ever takes place or a shovel ever hits the ground.

TP: That was the year that we were working on building the distillery. So I was like, “All right, well, God’s telling me, stop being mayor and start finishing building the distillery.”

ED: God said, “Go make whiskey.”

TP: Because you’re going to need it.

FURTHER READING: The Vermont city of Montpelier has a wood-fueled district heating system. As of February 2021, with fuel oil at about $2.40 a gallon, some of its users were grumbling about it not delivering the promised savings. Here’s hoping they’re saving money now that fuel oil is up over $5 a gallon. (Yikes.)

Here’s a little background also on New York’s new thermal energy network law and its history from Jay Egg, a geothermal expert who’s long been a proponent of community district heating systems. “Suffice it to say that geothermal heat pumps connected to thermal energy networks are the path forward as we decarbonize and electrify our building stock,” he writes.

SHOUTOUT: I’m saving a little space in the newsletter to thank everybody who signed up as a founding member to help Empire of Dirt get off the ground. This week, I’d like to thank Peg DiBenedetto for supporting the work I’m doing here.

Peg DiBenedetto was raised on a dairy farm in the little valley of Halcott Center, and is an eighth-generation resident of the Catskills. She is retired from the NYC Department of Environmental Protection, is a local author, and still lives on the land where she grew up. Peg has been involved with the Catskill Center for more than 50 years.

Here’s what she says: “I support Empire of Dirt on many levels: as a landowner, a lover of the Catskills, and Chair of the Board of Directors of The Catskill Center. Lissa Harris delves intensely into subjects. She reaches in with both hands, then deftly presents each topic in an intelligent and fully comprehensible manner. In short, she does the work for the reader on issues that are relevant to all of us who live or visit here and love the Catskills, our region, and life itself. Brava, Lissa! Keep it up!"

Peg, thank you, I’m deeply grateful. To the rest of you: If you’d like to support this newsletter, which is mostly free to read, please do subscribe.

PASS THE HAT: Feral cats are a big problem throughout the town of Middletown, which includes both Margaretville and Fleischmanns. Town board member Robin Williams has a GoFundMe and tip jars at local businesses to collect money for spaying and neutering them, which both helps keep the population under control and cuts down on feline misery. Toss ‘em a few bucks here.

Tips? Thoughts? Local Catskills-area fundraisers I can boost? Get in touch: empireofdirt@substack.com.